Art is a better way to experience something mathematical

AI in the music industry is nothing new. AI tools such as Google’s NSynth Super, Shutterstock’s Amper Music and Sony’s Flow Machines have been used by musicians to make music or simplify their music-making process.

In part one of our interview with Li Xiao’An, we got to see how a non-technical person gets involved in the development of AI as a subject matter expert. Follow us through the second part of our interview with him to understand how someone from the art scene views AI.

Huifang: A piece of AI-generated art was sold for more than $400k. What do you think of AI-created music?

Xiao’an: The fine art market has always been controversial because the million-dollar prices don’t necessarily correlate with some objective standard of “quality”. Someone probably looked at that and saw an opportunity for AI-generated art — it was certainly worth 400k to the person that bought it.

To tackle this question, we must ask ourselves two questions:

- Why do you make music in the first place? (To address the “threat” of AI-generated music)

- Do you like the AI-generated music that you are listening to? (To address its commercial viability)

I’ve heard AI-generated music that’s better than human-made music, but then just because a piece of music is human-made doesn’t mean it’s going to be any good.

Would I listen to these tracks? I haven’t really found one that I consider particularly compelling, but my lack of enthusiasm for them has no correlation with their value.

The technology is on the way, but I think it will take a little while before it gets to the point where it could truly ‘threaten’ my work, since there’s so much more to the job than just the production of the music. Most likely, we’ll first see the invention of AI-driven tools that I might actually use myself.

I don’t see any particularly convincing commercialization strategies in current startups focusing on AI-generated music, but I do admire the academic research that goes into it and find it extremely fascinating. I’d participate too, if the idea was right.

Huifang: What do you think about arts and data science?

Xiao’an: Data science allows us to make decisions that are based on real-world evidence, and thus more likely have some useful level of objective truth. In contrast, relying on our personal opinions and anecdotal evidence is much less likely to lead to robust, reproducible results.

One can make broad assumptions about topics such as market behaviour etc. from an experienced expert’s perspective. However, we need to fill the gaps with data to verify those assumptions and make credible conclusions.

If you are not verifying your assumptions, you will end up introducing high levels of personal bias. At best, this can be frustrating and ineffective. At worst, bias can cause problems for marginalized groups of people.

Musiio has allowed me to discover that musicians and artists share a lot of common ground with data scientists, mathematicians, physicists, computer engineers, etc.

A classic example of a person who successfully bridged the arts and sciences is Leonardo da Vinci, who was also a mathematician and inventor. In fact, the “arts and sciences” chasm is a relatively recent and invented distinction that only reared its head in the 19th century.

“Art” is simply the manifestation of highly complicated mathematics and physical principles that we enjoy through heuristic mechanisms we’ve developed such as the perception of beauty and aesthetics.

Huifang: We have instances where music is not made with an instrument. For example, the musical group Stomp uses the body and ordinary objects to make music. How do you distinguish between noise and music in such instances?

Xiao’an: Music is usually created with intent, and that intent is made known by the organization of pitch and rhythm into perceptible patterns such as a repeating 4/4 meter or a specific scale.

These can be determined by the presence of several specific mathematical relationships determining the amount of time between notes, or ratios that exist between fundamental frequencies that may appear in a piece of music.

With exceptions, the less organized a piece of music is, the more it sounds like “noise”.

Since AI that has been trained on massive datasets is to some extent a black box, we have to verify its accuracy through a human-intensive QA process.

There will always be a margin of error in AI, but humans are just as fallible. The main difference is that we can process 5 million songs a day, which means that the absolute number of correct results we can produce on a daily basis is far higher than humans could ever hope to achieve.

Huifang: Talking about the margin of error, what kind of bias do you see potentially happening or already happening?

Xiao’an: Due to resource limitations in the collection and curation of datasets, we currently tend to classify anything that’s not within a specifically Western set of genres, as “World” music.

As a musician, I find that fairly reductive. For example, in popular practice, multiple distinct genres have been grouped under the umbrella of Afrobeat in Africa. This has been a contentious issue to African artists, some of whom feel this does not reflect the true diversity of African popular music.

The problem is that it all depends on which system people are comfortable using. So, even if you had a system that is more technically correct than the other, the incumbent system will remain if the more accurate alternative is not accepted.

Huifang: Do you think AI can replace the jobs of human beings in the music industry? For instance, if the Hit Potential Algorithm could pick up a song potentially for commercial use, would that make the A&R executive redundant?

Xiao’an: Every advancement in technology has triggered a re-evaluation of our value in our specific roles.

Previously there were jobs that seemed to be important and required people to do them. But it turns out that these jobs could be automated and people are no longer required to do them.

Some people ask me, as a composer, if I feel like a computer is going to take away my job. But it is this same computer that enables me to do my job in the first place. It would be ironic for me to fear it.

When you take away all the tedious parts of my job, I get to think about the value I’m actually bringing to the table as a human being. With more time to focus on that — I can be much better at my job.

So, instead of fearing that AI will replace the jobs of human beings, think about what aspects of your job really need you, your brain, and your humanity specifically, and focus on getting really good at these parts.

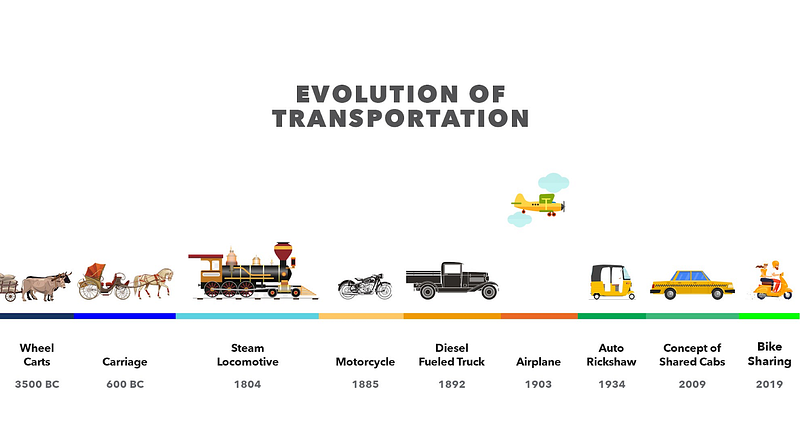

Similar to how we have adapted to the technology used in transportation, I agree with the views of Xiao’An that technology is here to improve our lives. The carriage driver’s job became obsolete but now we have taxi drivers. With the advancement of technology, we too make advances. Human beings are responsible for, and should always be mindful of technological advancement in order to prevent biases and misuse.